Trust and/or distrust, that is the question

This week’s blog is a three-part series on governing and governance in our day-and-age. Today’s blog is based on the results of Edelman’s Trust Barometer and how grievance affects the way we live. The next one will speak to the changes required to the way digital transformation is governed and overall managed. The last will speak to the difference of stakeholders and partners in a digital transformation vs a traditional change.

SelFou.digital

1/31/20253 min read

Before we dive in, we would like to explain why we are speaking about trust and/or distrust on a site about digital transformation. It is simple, the environment in which a transformation is conducted will have direct effect on the way it is transformed.

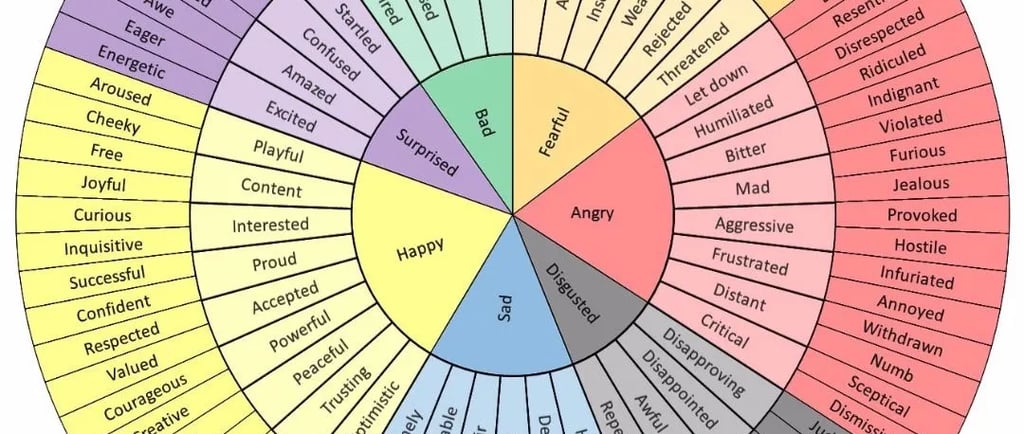

We included the Plutchik’s wheel of emotions as a image above. We invite you to read the article explaining the 8 basic emotions and get back to this blog after… it will probably take a different spin…

The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer speaks of grievance being the main issue for the upcoming year.

What we need to know:

Grievance, according to the Oxford dictionary, is: “a feeling of resentment over something believed to be wrong or unfair.” (one of the defitions)

The report continues by stating that “Sixty-one percent (of respondents or, 33 000 people from 28 countries) globally have a moderate or high sense of grievance, which is defined by a belief that government and business make their lives harder and serve narrow interests, and wealthy people benefit unfairly from the system.”

“In 2024, voters worldwide expressed dissatisfaction through the ballot box, turning away from traditional parties and incumbents in favour of alternatives that often-promised radical change. This shift reflects a growing sense of disillusionment with the ability of established political systems to address current challenges, from economic inequality and climate change to migration and geopolitical instability.

In 2025, incumbent governments will need to navigate an increasingly polarised and fragmented political landscape, finding ways to address the underlying grievances driving voter discontent. For traditional parties, this may require a re-evaluation of policy priorities. For emerging movements, the challenge will be to translate popular support into effective governance that delivers on the promises of change.”

The current tendency around the world is to elect governments that are more commanding than consulting. One could even argue that some are even domineering. What does that mean for our institutions and society?

Science Direct wrote an analysis on political domination and states: “Political domination not only strikes at the material integrity of a society, it also attacks the dignity of victims. Emotional well-being and a sense of self-worth can be hurt by armed and structural violence, as well as by witnessing degrading representations of oneself or being forced to perform humiliating acts. Such symbolic violence is meant to injure or destroy the recognition of mutual personhood.”

Further research on the side-effects of such an approach in our society and institutions the following was found and analysed:

Political style:

HBR in ‘Why we prefer dominant leaders in uncertain times’ explains: “A dominant (alpha) leader is generally perceived as decisive, action-oriented, and agentic, and therefore may be considered more appealing in such situations. In other words, endorsing a dominant leader in times of uncertainty is a response aimed at restoring one's sense of personal control.”

Policy making:

James Weinberg’s video on ‘Governance and policy making at an age of distrust’ shows how to counter the emotions to increase trust or counter it so governments and institutions can still function and move forward.

Vox further explains our current situation:

“In Europe, the 2015 refugee crisis played a central role in the story. That year, violent bloodshed in countries like Syria and Afghanistan produced the single greatest number of refugees since World War II, many of whom fled to Europe seeking a better life. The centrist European establishment, led by German chancellor Angela Merkel, chose to welcome them, creating an opportunity for far-right parties to increase their support among Europeans uncomfortable with a massive influx of people who looked different, prayed differently, and spoke different languages.

The effect was swift and striking: Data from The PopuList, which catalogs far-right electoral support in European elections since 1989, shows a spike in these factions’ support around the continent in the wake of the crisis.”

What is far-right today, may be far (or not so far)-something else tomorrow. Based on our last blog, how AI stays accurate with these behavioural shifts may have something to do semiologists keeping up. Much to the detriment of our in-house semiology, it will most likely be having the AI analyse the socio-political pendulum effect to predict the behavioural shifts and forecast the far, or not so far-somethings of tomorrow.